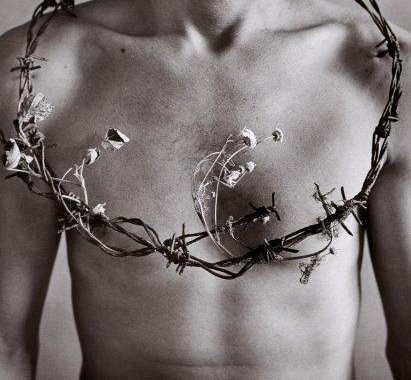

“Where there is sorrow there is holy ground”

Oscar Wilde (1854–1900)

How do you decide your final resting place? Is it better to be scattered over the ocean or to seek eternal rest in the ground? The question can be troubling to consider. I have an unfair advantage in questions of this nature. One specialized aspect of my business is the design of cemeteries. This immediately strikes people with a chill. It is not as you may think. In the past 10 years I have master planned over thirty cemeteries from Baton Rouge to Chicago. Our society has lost connection with the intrinsic meaning of cemeteries. It is a fascinating art to explore.

Do not be mislead death is a business, a big business. There is more accounting and statistical analysis in the cemetery business than is almost any other type of land development business. I can tell you for any cemetery I have worked on; the changing community demographics, the product type absorption rates, the annual land depletion, the price point strategies and shifting ethic burial trends. Design of cemeteries is an unusual mix of park planning and subdivision development. They are little cities for the dead. Every decision is calculated in terms of economics. The old rule was that a cemetery would hold forty years of open space for growth before it considered the asset as potential real estate for sale. Today the trend is moving toward ten years.

A couple of basic facts are important when considering cemeteries. There is so much public opposition that less than two or three new cemeteries open each year in the United States. Compare this number to the almost 1,000 golf courses under construction or in planning for 2005. No one wants to be the first one to be buried in a new cemetery, so sales are flat for the first 20 to 50 years. We all want to be buried in places that have social and cultural significance. New cemeteries don’t provide us this connection with history. The aging baby-boomers and World War II veterans are dramatically increasing demand for new cemetery space, but this growth trend is being offset by the increasing trend of cremation (the evil foe of the cemetery business). Interestingly enough cremation trends are increasing only in certain geographic regions. Consider the difference; one acre equals 500 standard lawn crypts or 40,000 cremation memorials.

The second unique aspect of cemeteries is that by state law they need to endow a sufficient trust to provide for perpetual care of the grounds. The states were tired of cemeteries selling all the lots and then going out of business leaving the perpetual care to the public. The process of projecting perpetual care reserves is exceptionally complex, one more reason for more accountants. Sales in cemeteries tend to peak when the grounds are 80% developed. Sales of the last 20% of the space in a cemetery will slow to a trickle, when all the good sites are developed and groups of lots for families are harder to come by. The last opportunities for sales in a cemetery are the “orphans” or single lots scattered throughout the grounds. Toward the end a cemetery closes burial operations and the maintenance is managed by the trust. Historic cemeteries may convert to service the tourist industry to supplement income for operations.

As cemeteries develop older sections are maintained basically the same forever. A cemetery is one of the few designs that will remain unmodified for hundreds of years. The process of contacting relatives in order to move bodies is messy and difficult; as a result it almost never happens. Of all the works of art I have designed, cemeteries will remain my design legacy long after all the other spaces have been destroyed. I have no illusion that my built works in cities will persist, they are subject to political whims and social fashions. Look at all the great works of Dan Kiley or Lawrence Halprin that are lost to society less than 40 years after completion.

The modern cemetery movement originated in the 1860’s with the design of Mount Auburn Cemetery outside of Boston. This was to be America’s first rural cemetery because of new health codes and a lack of space in urban churchyard cemeteries. Trinity Church Cemetery in downtown New York is almost eight feet above street level, a result of burial of thousands of thousands of bodies over the years. At one point in winter when bodies couldn’t be placed in the frozen earth, they were stacked so high in the morgue at Trinity Church that the walls collapsed spilling hundreds of bodies onto the public street. This prompted a yellow fever scare which helped the passage of legislation in New York outlawing the burial in churchyards within the city limits. The rural cemetery trend paralleled the parkway and boulevard movement on the east coast. Traveling to the countryside by the new contraption called an automobile allowed families to picnic in cemeteries and visit the recently departed. Cemeteries were a form of recreation as was driving. It seems both activities have lost some of its original glamour.

The federal cemetery system was established during the civil war to help with burial of civil war dead. Following the ratification of secession by Virginia, federal troops crossed the Potomac and, took up positions around General Robert E. Lee’s estate. Lee’s property was confiscated by the federal government when property taxes levied against the estate were not paid. Brig. Gen. Montgomery C. Meigs appropriated the grounds June 15, 1864, for use as a military cemetery. Miegs was so outraged by General Lee’s role in loss of federal soldiers; his intention was to render the house uninhabitable should the Lee family ever attempt to return. He ordered the remains of 1,800 Bull Run casualties to be buried in rose garden of Lee’s estate. We now know this sacred ground as Arlington National Cemetery.

Society misunderstands that cemeteries are valuable cultural resources. They are the historical records of the nation and in many cases they may be the only record of some communities. Cemeteries are precious open space in many densely populated urban centers. Cemeteries embody our customs, beliefs and traditions. Myths and traditions mingle in that final path that leads to death. In Jewish Cemeteries it is customary to place a small stone on the crypt or headstone to signify that you were there. A sign of respect that has it’s origins in biblical times. When a traveler past a grave, by custom they would add a few more stones to prevent the body from being scavenged by wild animals. The immigration of Russian Jews to the U.S. after the fall of the iron curtain is apparent in the cemeteries around Philadelphia. Russian Jews tend to use black granite headstones with a portrait of the departed etched on the surface. These sections of cemeteries look like crowds of ghosts as the black and white faces peer back at you.

As for me the question was unsettled for a long time. I will forever find my soul in the ocean. However there remains a need to leave a legacy that I did exist long after I’m forgotten. Do I finish life as the nomad I’ve become? Can I be satisfied tied to no place and time without a place for later generations to discover me? Should I be buried like a warrior of the high steppes with no marker, scattered to the air as dust? Cremation seems so temporal without permanence. I have always had a primal connection with the earth. To be grounded means to be sure and strong. I like the idea of having a place on this earth. I like the idea of being able to come to that place before death to reflect on life. I can see myself lying in the grass watching the clouds go by. It seems comforting to know that I will return to that exact spot when the trials of life are over. It is not sad; it is a source of power and strength to continue to distance me from the final resting place. I like the location I designed it; it represents the things I value. What do you think? Come by and see me there some sunny day, come by before it’s too late. Maybe my epitaph should read “Change This Place, Over My Dead Body”.

"The tree of deepest root is found

Least willing still to quit the ground:

’T was therefore said by ancient sages,

That love of life increased with years

So much, that in our latter stages,

When pain grows sharp and sickness rages,

The greatest love of life appears."

Least willing still to quit the ground:

’T was therefore said by ancient sages,

That love of life increased with years

So much, that in our latter stages,

When pain grows sharp and sickness rages,

The greatest love of life appears."

Hester Lynch Thrale (1741–1821)