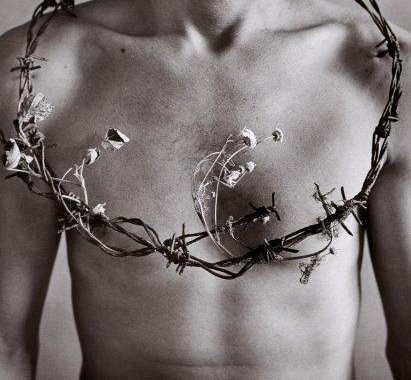

There is a sinister and insidious process plundering the great public spaces of our nation and few seem to neither notice nor care. Public apathy and ignorance has given this plaque on our sensibilities a foothold challenging the value and even existence of great public spaces. The first victim executed in this all out assault is the creativity of design. It has taken years of close observation to understand this subtle shift away from civic responsibility to the absolution of risk in the construction industry. Society has entered a period of future uncertainty where the bureaucrat and accountant are responsible for the artistic and design values of public spaces. Around the office, we call this new period the “Culture of No”. I am deeply troubled by loss of opportunity to create public spaces of meaning and relevance to further generations. Consider what our world might look like with out Central Park in New York or the Mall in Washington DC.

The creep toward chaos began thirty years ago when in a short sighted attempt to shed liability for the construction process the American Institute of Architects (AIA) positioned architects out of managing the construction process. The thought was if architects are going to be sued for managing the construction process then architects just will limit involvement and inherently shed their liability. This stupid act of contrition has relegated architects to a meaningless and ineffectual seat in the back of the construction industry bus. Once the master builder, the architect abdicated the only meaningful way of controlling quality assurance on the construction site and in the process exponentially increased their liability and risk of litigation. The architect is no longer at the table in a position of authority to defend the design or provide a rational for civic values. The AIA’s decision is one of the world’s greatest blunders. The only logical response to construction liability was for architects to take full control of construction process and insert themselves deeper into on site management. Alas this abdication created a vacuum to fill a fundamental need required by the construction industry and spawned the creation of a new profession, the construction manager.

While a few enlightened architectural firms recognized the opportunity and added construction management as a specialty service, most walked away from the table, leaving general contractors to fill the void. The fox is now running the henhouse as the industry spirals into an abyss that we may never recover from. Recognizing the enormous opportunity to limit risk and reap huge profits general contractors jumped at the chance to control the construction process, especially the budget. Within a short period of twenty years construction managers or what we call “general contractors at no risk” have inserted themselves into the construction process ahead of architects. While this seems benign the result is catastrophic, impacting every decision made during the conception and design of a project.

The sacred one on one relationship between the owner and architect in which design values are established, where art and civic responsibility are discussed, where the relevance of context is formulated no longer exists. Today the discussion managed by the construction manager constantly challenges every decision of the architect on the basis of cost or construction efficiency, before an architectural vision is born. It was once said that an idea at birth is most frail and ever so delicate that it can be easily killed before it has a chance to grow. In the current environment ideas never has a chance to be realized because it is suffocated immediately by the ponderous weight of substandard budgets and schedules exclusively defined by inept construction managers. The industry has evolved to the point where the owner and construction manager establishes a project budget before architect is even selected.

Consider the problem in this approach, a contractor with no training in design is formulating a budget before any exploratory investigations are begun. Without any real interest in design or commitment to artistic expression the construction manager assembles a series of simple white box assumptions which are primarily focused on square foot costs of other uninspired completed generic commercial buildings recognized only for their brutal ugliness. The budget is normally based on the least complex or vanilla solution. There is no consideration for civic responsibility or really any understanding of site context as the construction manager establishes the budget. The motives for the construction manager to set the bar as low as possible are oblivious, because in most cases it will be that same construction manager in the role of general contractor which will be responsible for delivering the project for that budget. In order to make it easy to achieve the goal, all unnecessary complications and complexities are avoided. The construction manager which is really the general contractor is now in position to play both sides against the center. Keeping the bar low and the pricing high allows the construction manager to reap huge profits at the expense of the public.

Once this uninformed vanilla budget is established it becomes law with few exceptions and the entire design process enters the value engineering (VE) stage. Early in my career value engineering was confined to the small world of bringing a project back into budget after prices were received by a competitive bid process. Today VE is a constant process of striping integrity from a project before it is fully conceived. The joke around the office it that “value engineering is of no value and it ain’t engineering”. For example a recent project was budgeted without geotechnical investigations. After the geotechnical engineer discovered a high groundwater table it was necessary to include a foundation dewatering system which would cost $500,000. Guess what the original budget established by some uninformed manager did not include a dewatering system, so it becomes the responsible of the architect to gut $500,000 out of a project which is already without frills. No discussion that this omission should have been considered by the construction manager. No discussion that the budget should be increase to accommodate the unknown site conditions. No, just cut the public improvements, just cut the plazas, just remove the grand entry, and just make everything we build look like a cheap target store. The worst of all is the construction manager doesn’t see anything wrong with that. A cheap target store is much easier to build, much more predictable to cost than a beautiful work of architecture.

In another project of significance we were asked to submit a proposal to a nationally recognized architect. We explored the beautiful and elaborate preliminary concepts developed by the architect, estimating in detail what each component would cost based on similar projects we have completed around the nation. When we were done we estimated the budget to achieve the architects schematic vision was about 1.5 million dollars. Presenting the estimates to the architect, the construction manager piped up and said they had only budgeted $175,000 for the work, a tenfold difference. Somewhat in shock I asked “What is that number based on? Did you even look at these drawings?”

The construction manager said “We gave the drawings to Mullet Contractors to give us a price. You know the inept, unqualified group that has been in court constantly because of construction fraud. You know that group of thieves that has been kicked off every project in the metro because they don’t know their ass from a hole in the ground.”

“You mean you accepted this unqualified unresponsive number without validating it and this was the basis for your entire construction estimate? There was no information on materials, no specifications, no allowances, no established schedule or no direction given beyond this rough sketch?” I ask not believing how this is not considered a criminal act.

With total lack of concern he replies “Yeah, that’s how we did it and no we won’t change it”.

How does one ever begin to close the distance between $1,500,000 and $175,000. What will the public get from the incredible artistic vision by the architect? They will get another cheap looking Kmart with a parking lot, never a functioning urban space which creates great cities. The saddest part is that if the owner really knew the cost early in the process, he would have authorized the additional cost, but the gatekeeper of the budget is the construction manager and his culture is no. Whenever the construction manager needs to increase the budget in order to build the minimum requirement, they blame the overage on the architect and get to increase their fee to manage the overage.

In a recent example on an important civic building in which hundreds of thousands of patrons will visit each year, we discussed with the owner over four months the budget to create a grand public space respectful of the grand public. Our assumptions were slightly over 2 million dollars, again based on extensive experience and knowledge. When out of the blue we receive an email from the construction manager blistering us for not designing with any concern for budget and that the design team was being totally irresponsible. Confused we called a meeting asking for clarification, knowing we were working off our budget assumptions discussed with the owner. In the meeting the construction manager finally had to reveal the secret budget assumptions they were working with and for the first time provided line item budget pricing. They estimated that the civic masterpiece costing hundreds of million dollars on a large difficult site would only require $650,000 for everything around the building. When pressed on what was the basis of that estimate? They only offered that it was an unsubstantiated guess without supporting documentation. Let it be known that we were not dealing with a new inexperienced constructor manager but one of the top ten largest groups in the nation. Once again an inept uncaring untrained construction estimator is making decisions about how are cities will be designed?

In each of these examples, the construction manager defined an unrealistic budget which eliminates all opportunity for public space. They achieve credibility because everything they build is basically cheap and ugly, and when a challenge to their budget is made they can trot out fifty examples of cheap buildings as comparison. How can they get away with the destruction to our urban environments while lining their pockets with huge profits? The answer is easy; they have a facilitator, the risk avoidance governmental bureaucrat.

The culture of no is endorsed by the public officials who are responsible with protecting the public good. Bureaucrats are a relatively benign group of wall flowers devoid of artistic appreciation. They are simple managers that do what they are told and only worry about the criteria under which their performance is measured. Unfortunately we do not ask bureaucrats to create urban spaces of great value to society, we ask them to manage projects that are delivered in budget, on time and that adhere with the rules. As a result government bureaucrats deny any discussion which could threaten the schedule or more importantly the budget. This myopic fear of not delivering a project on budget makes the bureaucrat unable to adjudicate project objectives that require advocating for increased budget funding. The culture of no places the risk avoidance governmental bureaucrat as the gatekeeper of public benefit. When the process combines the construction manager’s personal agenda to keep it simple to make money and the bureaucrat’s inordinate fear of challenging the process, the result is a culture of no.

What was once an infrequent imposition on creativity has now developed into a process that rewards inept managers, greedy contractors and ignores the public good. The future of social environments is uncertain. Having considered the trend for many years, I’m pessimistic about the system changing anytime soon. The architect is helpless, the public has no advocate, the construction managers won’t relinquish control and the bureaucrat won’t do anything to be criticized about so the urban environment will continue to be a victim of the culture of no.

“The perfect bureaucrat everywhere is the man who manages to make no decisions and escape all responsibility.”

Brooks Atkinson (1894 - 1984)