"In the hearts and minds of the people, the grapes of wrath were growing heavy for the vintage."

John Steinbeck (1902 - 1968)

The Grapes of Wrath

The sun peaks through the soft white clouds drifting in a crystal blue sky, highlighting the lush green slopes of the Blue Mountains providing a stunning backdrop to the morning. The rolling foothills frame the waving green fields of alfalfa hugging the bottomland. The views are expansive extending miles as white tail deer and wild turkey dot the foothills out of reach. Vines precisely trussed along thin galvanized wires secured to weathered fence posts dance over the slopes providing a delightful visual harmony.

Standing next to me is a tall thin man with a proud Marlboro jaw and piercing eyes the color of a clear blue sky. He is dressed in jeans and a simple western style shirt with pearl snaps as he leans on the hood of a big new Ford pickup truck. Facing the morning sun the salt of age glitters in his black pepper hair as he shades his eyes looking over the land that has been in his family for generations. His love of the land is apparent as he describes the history of every small feature of the field below while his other hand gently points out the landscape as if caressing the nude back of a beautiful woman.

According to the historical society, “the Walla Walla Valley was one of the first areas between the Rockies and Cascades to be permanently settled. Lewis and Clark traveled through the county in 1805 and 1806, making friends with the Walla Walla Indians on their way to the Pacific Ocean. Fur traders carved out early settlements and trading posts and the early 1800's. Missionaries Marcus and Narcissa Whitman settled here in 1836”.

“With the lure of nearby gold in 1860, Walla Walla quickly became a commercial, banking and manufacturing center, and soon became the largest city in Washington Territory. The City of Walla Walla was incorporated in 1862. After the gold rush ended, farming anchored the community. It remains vital to the current economy. As a group, Walla Walla County's farms are the oldest in the state. More than half of the County's 47 centennial farms were established before 1875”.

Years ago, many Native American tribes inhabited the region, including the Walla Walla, Nez Perce, Cayuse and Umatilla. Walla Walla is a Native American name that means "many waters" or "small, rapid streams." Standing on the slopes of the rolling hills, his strong baritone voice softens as he describes how the emerging wine industry has changed the value of land which has risen tenfold in less than a decade. Even this dramatic increase in land value still represents about one tenth the cost per acre compared to Napa Valley, so the development pressure will remain unabated for years. This increase in value in the family property has created a tax inheritance burden which can not be carried by his children and grandchildren, so after considerable soul searching the family has decided to develop the property into environmentally sensitive single family estates. The property is surrounded on all sides by some of the finest vineyards of the state and quite possibly the nation.

Climbing back into the truck for a view from the far ridge, he begins to tell me about how he began growing grapes for the local wine industry almost 17 years ago. Providing a stunning backdrop, the Blue Mountains frame the valley that is home to more than 60 wineries and as many vineyards, all of whom work hand in hand to produce world class wines of exceptional character. Excellent examples of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Syrah have earned the Walla Walla Valley national and international acclaim in recent years. Other grape varieties such as Chardonnay, Semillon, Cabernet Franc and Sangiovese also produce wines of subtlety, balance, and complexity. In the fertile ground between the vineyards are massive orchards growing hundreds of acres of cherries, apples and plums as well as onions and potatoes. We pass a large round promontory called Mount Fuji which is a single orchard of a hundred acres of Fuji apples most of which are exported to Japan.

Passing weathered basalt outcroppings as we climb a bumpy gravel road the conversation quiets giving me the perfect opportunity to indulge my lifelong fascination with wine and grapes. Speaking with great passion, he patiently answers my continuous stream of questions. Selecting the right location for growing grapes is a combination of art and science. The grapes are located on the slopes when they received an optimum balance of exposure to the sun and shelter from the heat. The vineyards occupy slopes to cool the grapes in the evening when cool air flows down from the hilltops. The bottomland valley stores heat during the hot summer nights providing the grapes little relief, so it is rare to see any vines on flat bottomland. Most of the vineyards are laid out so that the rows run north and south providing foliage maximum exposure to the sun during each day. Each vineyard has a yen garden like appearance as if sculpted by a giant rake.

Walla Walla has developed a soft sustainable viticulture practice called “Vinea”. Attempting to establish Walla Walla as a leader in sustainable viticulture, the growers and vintners formed The Winegrowers’ Sustainable Trust which is a voluntary group that have embraced a covenant with environmental, economic and social sustainability concurrent with their production of grapes and wine. The Trust defines sustainable viticulture as “ecologically sound, economically viable, and socially supportive. Because it is more a philosophical approach to viticulture than a set of farming practices, the specific practices vary depending on the specific environmental and social issues important to an appellation.”

The Trust describes how Vinea’s sustainable viticulture practices compare to organic and biodynamic farming practices. “Viticulture can be “sustainable” without being “organic” or “biodynamic”. Also, some organic or biodynamic operations may not be sustainable. Organic farming certifies that the grower has excluded the use of any synthetic agricultural chemicals. Biodynamic farming combines the tenants of organic farming with practices that are intended to influence the metaphysical aspects of the farm (such as increasing vital life force), or to adapt the farm to natural rhythms (such as planting seeds during certain lunar phases) as well. However, approaches to management of healthy soils can be similar between the different farming systems.”

Unlike Napa Valley these vineyards are not cultivated accommodating a cover crop that builds soil fertility and biology, but also provides habitat for beneficial insects which control pest populations. An important consideration in grape production is frost protection with many of the vineyards being equipped with large fans and misting systems. Growers will spray the grapes with water when temperature approach freezing generates heat when the water turns to ice protecting from grape from damage. In “Vinea” leaving a cover crop provides more surface area for the water to cling to enhancing frost protection. Many of the vineyards include the tradition of planting a single rose bush at the end of the row of vines. Historically the rose was planted as an early indicator of frost damage and before the advent of modern technology a grower would know that actions to protect the vineyard from frost were necessary if the rose petals started suffering.

Some of the wineries grow their own grapes but most purchase each season’s grapes from growers. Wineries will contract with the growers to produce grapes on long term leases from a specific acreage of in a vineyard. Quality-oriented wineries now negotiate grape purchase contracts based on acres, rather than sugar level and tonnage. This allows the winemaker, rather than the vineyard owner, to decide how much fruit the vines will carry and when the grapes are ready to begin harvesting. The average cost for grapes in the valley at about $7500 per acre and the yields can range from two to twelve tons per acre. For quality wines from the Walla Walla valley the yield per acre will be managed at between one and three tons.

Vineyards vary in the spacing between the rows and between the individual vines. Depending upon the age and variety, some are more productive per vine than others, some produce larger clusters of fruit and some yield more juice per pound of fruit. Wine makers and their facilities also vary in the amount of juice they are willing or able to squeeze from the grapes. In rough averages when considering grape production one pound of grapes equal about 4.5 clusters with between 40 and 60 grapes per cluster. In other words it takes 9000 clusters to equal a ton of grapes. One ton of grapes will produce 60 cases or 720 bottles of wine. So a single bottle requires between 440 and 660 grapes. On average in the Walla Walla valley one acre of vineyard produces from 2250 to 4500 bottles of wine.

The vines are a very aggressive crop that must be prepared early each year and merit special attention. Each stage requires meticulous work, and traditional skills primarily focused on manual labor. The first element for controlling production to come: winter pruning, followed by trimming that suppresses excess shoots in the spring. Each different grape variety undergoes a maturity test which defines optimum maturity according to the quality of wine desired.

After the roots and stalk have developed, the untended vine would grow wildly, spending most of its energy on spreading its shoots and tendrils. If left to nature, a single vine could cover as much as an acre of ground, with the roots developing wherever the branches touched earth. In ancient times, this was allowed, a practice called layering. Normal practice of the time was to prop up the vines to prevent the fruit from rotting or rodents from eating it. The Romans even planted elms in the vineyards, simply to support the vines. These ancient viticulturists came to realize that, instead of allowing the vines to grow outward in all directions, training the vines in rows with canes pointing upward produced better, more even-ripening grapes.

Jim LaMar an expert in wine production notes, “in 1860, Dr. Jules Guyot published the first of three treatises describing regional traditional vinicultural and viticultural practices which documented the cultivation practices of vineyards which had gone unwritten for the previous five thousand years. It wasn't until the recommendations of Guyot, however, and the massive replanting due to phylloxera that vineyards typically had an orderly, row by row appearance”.

In describing the care of the vines he writes, “it was discovered that better-quality fruit will grow on vines that are pruned back to distribute the bearing wood evenly over the vine. So, in the winter months, when the leaves have dropped and the vines are empty of sap, they are pruned back almost to the main stem. Pruning is an art of delicate balance. Pruning also facilitates cultivation, disease control and harvesting, when the vines are trained to grow in a particular shape. It is a skill that requires experience and judgment which is only done by hand. There are only two basic pruning methods: cane-pruning and spur-pruning, also known as head-pruning. Spur-pruned (head-pruned) vines are usually found in older vineyards. Spurs are the canes (branches) trimmed back to only a pair of buds. Each bud will become a shoot which grows to a cane that bears the crop. In the winter after the harvest, the top cane is removed and the bottom cane trimmed back to a two-bud spur. Spurs are often distributed around the head of the vine, like spokes around a wheel. The top is left open for sun-exposure and this method often leaves the vine in somewhat of a "goblet" shape. These vineyards can only be hand-harvested. Some head-pruned vines are converted after a time to grow on trellis wires. Head pruning is used only in warm growing regions, because it encourages massive vegetation that slows ripening. It also makes harvesting more difficult.

In the cane-pruning method, from one to four, one-year-old canes, each with six to fourteen fruit buds, are trained along trellis wires. This is also referred to as "cordon" (French for "arm") pruning, since the vine looks as if it is stretching out it arms. Because one-year-old canes must be used to bear the fruit each year, the cane-pruners therefore must train the current fruiting canes and at the same time consider which spurs to train for next season's fruiting canes. In France, a single cane with a single spur is known as Guyot simple pruning and two canes and spurs as the Double Guyot, because Dr. Guyot was so influential in promoting these methods. Modern trellising methods vary by variety, geography, geology, harvesting methods and winemaking style! Two, three or four-wire, vertical, lateral, cordon and other configurations of trellis may exist in neighboring vineyards. There are stakes made of wood, metal and those combining the two materials. The different patterns primarily affect exposure to sun and wind and accessibility of fruit for hand or machine harvesting.”

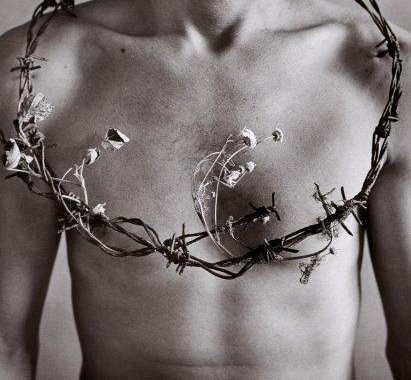

Vines respond to early pruning and the reduction of leaf foliage by producing flower sets. Grapevines produce fruit only from one-year-old wood, called a cane; thus, long or short canes should be retained during pruning. Although 60 or more buds can easily be left on a grapevine, a crop of 3 tons per acre cannot be expected unless the vine has sufficient vigor to support such a fruit load. To determine the potential fruit capacity of a vine at pruning time, growers can use the concept of balanced pruning. The principle is valid for all grapes in general, but varies in magnitude from one cultivar to another. Growers control the grape yield and quality per acre by systematically dropping fruit or selectively pruning the grape clusters whereby concentrating the flavor and intensity into fewer grapes. Depending on climate, temperature and rainfall the grower may drop fruit up to three times before harvesting. The key to flavor and intensity is stressing the vine so that it works hard and struggles. This requires precise control of soil moisture levels through automated irrigation systems. The worst thing that can happen to a crop of grapes is to endure a wet rainy period just before harvest, which will wash away or dilute the intense flavors of the maturing grape. Varieties differ in the amount of heat required to mature their fruit. One-hundred to 120 days after flowering, the grapes should be ripe. The harvest may start mid-August in warm areas, to late-September in the coolest ones.

An important indicator of grape maturity is the sugar level. Sugar (more exactly sucrose) is measured in the United States using the Brix scale, which uses specific gravity to determine the percentage of sugar, by weight. A 25 °Brix solution has 25 grams of sucrose sugar per 100 grams of liquid. Or, to put it another way, there are 25 grams of sucrose sugar and 75 grams of water in the 100 grams of solution. In Walla Walla wine grapes are normally harvested between 21° and 25° Brix. From the 1960s through the 1980s, wineries often paid growers based on sugar content and the tonnage. Fruit maturity is not, however a simple matter of sugar content. Acid content is every bit as important to quality and flavor and even more so to aroma constituents. Grapes will respire acid (especially malic acid) as they ripen and this loss is greater in warmer vineyard locations.

As grapes ripen, sugar, color and pH increase as total acidity decreases. For the highest quality wine, grapes need to develop aroma and taste characteristics that only result from physiological maturity and sugar-acid balance. Some signs of this maturity are the browning of the grape seeds (pips) and lignation, which is the browning and drying of the berry stems. But by far the most important indicator of maturity is the taste of the grapes.

The sun had started to sneak behind the Blue Mountains staining the sky with pastel hues when I finally realized I have been peppering my guide with questions for almost eight hours. In an understanding and mentoring manner he endured my barrage of inquires because we were two kindred spirits sharing a deep love of the land with all its abundance and wonder. He had recognized in me, like himself a primal need to be grounded to the land, to breathe in every summer breeze, to dig my hands deep in the soil just to smell its rich perfume, to find purpose and sustenance in caring for the abundance of the land. In the process we have walked between the rows of vines examining the clusters in great detail as if they were masterpieces of art hung in a gallery while local laborers set about the first dropping of fruit. We passed each new winery in an old barn or convert shed while he explained the type of wine being produced, the production volume in cases and more other often than not with a humble voice and cheerful glee in his eye he would whisper that he supplied those grapes.

Rounding a small hill the town is visible as my guide makes the suggestion that we meet his wife in town for dinner at one of the local restaurants. Embarrassed he qualifies his invitation with a comment that the town needs more quality dining establishments. Arriving at the small restaurant we are escorted to a small table outside on the terrace facing the Blue Mountains where his wife is already seated waiting for us. Quickly we polish off the bottle of chilled Chenin Blanc which his wife has been drinking. I’ve never been able to identify all the subtle flavors and aromas, although my thirst and the long day gave the wine a delightful sweet flavor of honeysuckle. You will never confuse me with a wine snob, because I drink wine not as status symbol, but because I enjoy it so immensely. Unfortunately the only flaw in my thinking is the fact that the better the wine is the more I like it.

In a short few minutes the Chenin Blanc was gone. My guide immediately reaches for the wine list and asked me what I would like to drink with dinner. The question is absurd to me because the answer is so obvious. “What I want to taste some of the grapes you have grown.” Slightly embarrassed again he admits that the wine list contains over twenty vintages that he was produced grapes for. His wife offers her thoughts and sits back in her seat smiling knowing the answer. After scanning the list for a moment he calls the waiter over and tells me “I think you might like this one.”

The dinner conversation is pleasant and comfortable while the waiter brings the bottle back and opens it pouring the claret nectar into each of our glasses. Without pretense I swirl the wine around in the glass to open the bouquet slightly and take a sip. In order to savor all the richness I close my eyes. There is no need to break the silence of the moment as a smile clings to my face. No word can better express my contentment than sitting in silence in the presence of kindred spirits with the fading light coloring the mountains in the distance soft purple hues. I pick up my camera a take a picture of the sunset and recall the old saying “If only you could capture time in a bottle”, at least for the moment I believe they did.

Robert Louis Stevenson